Greetings! In the past several months, many of you have joined this little think space. Welcome! I’m a medical anthropologist and professor who has been working on trying to put Long Covid into a historical perspective over the past several years. I’ve been writing about this research so that I can share my take on what I’m learning and how I’m thinking about the complex body of evidence and experience in real time. Long Covid is an urgent political situation; however, living with a complex chronic illness like Long Covid is an old story.

For two decades, I’ve been thinking about the complexities of living with complex chronic illnesses, and challenging the idea that health and illness are tied up in one dis-ease that is the thing that makes the body spiral into dysregulation. For years, I used the prism of trauma, distress, and diabetes—as social, psychological, and physical markers of distress that are so often entangled—to understand these complex and fascinating interactions that are so often overlooked in clinical medicine. They are overlooked because of systemic problems (like clinicians being too overburdened by time and pressures) as well as cultural problems (like the overt focus on pinpointing disorder to treat or cure instead of care for living within a new pace).

In my anthropology training, I spent a great deal of time thinking about what it means to live with chronic illness while dealing with all types of adversity. Many people I met experienced all sorts of trauma in their pasts and were still navigating waters of adversity. But often this work was in association with conditions that were clearly verifiable—like type 2 diabetes and breast cancer. Working within the grey areas of conditions that are largely unverifiable (like Long Covid) has been a remarkable journey. I’ve nearly completed writing a book on the subject, tentatively entitled: Invisible Illness: A History, from Hysteria to Long Covid, which focuses on the biological nuance of conditions that are idiopathic (and often perceived as psychological even when there are complex biological processes at hand). This project has led me down several rabbit holes—many that I had to eventually delete from the book.

Now that my book is nearly ready for final review with the editorial board, I’m going to publish some of the interesting stories that were unfortunately cut. Some of these stories were cut simply because there were too many stories that I’ve tried to incorporate and I had to pare down. Many of these stories come from the more than 150 formal interviews (or hundreds of informal conversations) I’ve had with people living with invisible illnesses (which are often but not always unverifiable).

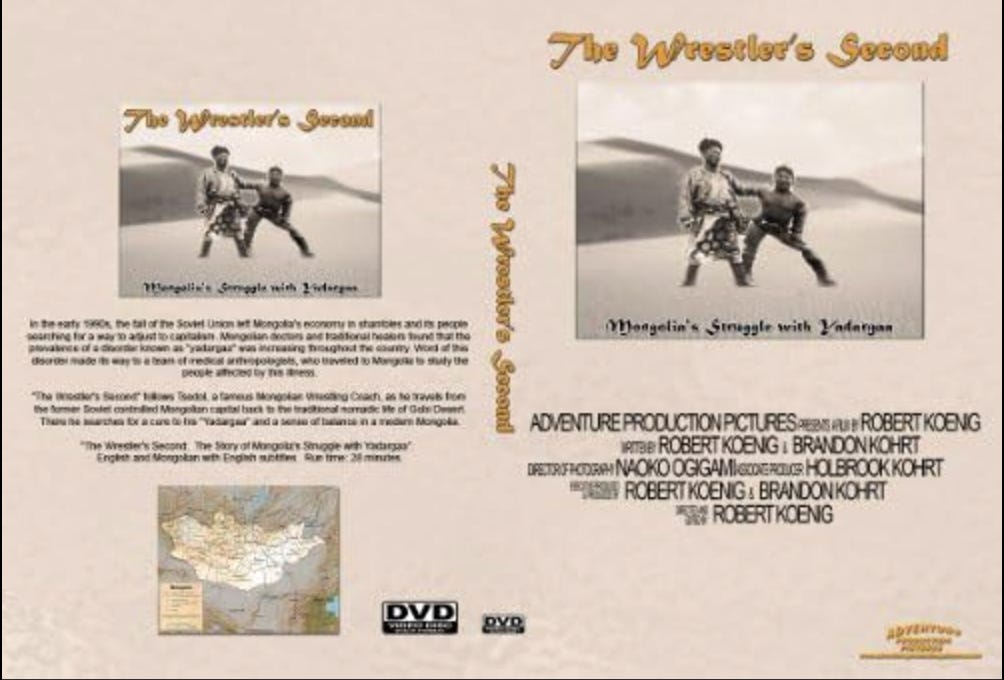

The one I share today, however, is a historical one. This story is based on some earlier work by my old friend Brandon Kohrt, a medical anthropologist and psychiatrist who has spent most of his career working to improve mental health care around the world for people who have experienced extraordinary trauma. More than two decades ago, however, when Brandon was in medical school, he orchestrated a project with his brother and best friend in Mongolia that investigated a complex chronic condition called yardargaa. This project turned into a documentary film called The Wrestler’s Second.

I have long discussed my research and new ideas with Brandon. For fun, I revisited this old film and was struck by some of the similarities and differences in how people framed yadargaa versus complex chronic conditions that are more common in the U.S. I found it interesting to revisit this early project he engaged with, which was foundational to his thinking about what complex chronic illness is and how deeply it is entangled with politics, social context, viruses, bacteria, and the thresholds people face while trying to navigate the human experience.

Yadargaa: A Complex Chronic Condition in Mongolia

On the cusp of the millennium, one of Mongolia’s most famous wrestling coaches fell sick. Deemed one of 28 of Mongolia’s Grand Zasools (or coaches) in Mongolian wrestling, Tsoodol had to retire from this work as his health deteriorated. This was during a transformation of Mongolia’s economy from communism to capitalism. This rapid transition of the way in which people perceived and lived in the world was reflected in Tsoodol’s sickness, diagnosed as yadargaa. Yadargaa may be understood as a lack of vitality—defined by the belief in Mongolian medicine that the khii (vapor or energy) becomes imbalanced in some way, such as hot or cold, up or down. For instance, a cold and noisy environment increases khii. Black tea, coffee, and rice elevate khii. Excess of these things makes your nervous system imbalanced. Yadargaa is translated as the khii increases diseases. For Tsoodol, it was perceived to be the economic policy that turned his world upside down and caused yadargaa.

By the year 1999, Mongolia was undergoing a rapid economic transition. For centuries Mongolia had very few people when compared to its vast land. One-third of the population reside in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. Another third resides in small remote towns. And the last sector of society lives nomadic lives, herding sheep, goats, camels, horses and yaks. It was a communist nation for six decades (1924-1990), when life expectancy nearly doubled and literacy rates rose to 96%. Women worked freely and healthcare was widely available. By 1995, however, poverty rates shot up by 27% and average income dropped by a third—crime increased rapidly and people got sicker. It was particularly difficult for women, aging Mongolians, and those who lived in the capital because work was hard to find.

Brandon Kohrt met Tsoodol through physicians he worked with in a hospital in Ulaanbaatar. In 1999, Brandon spent several months in Mongolia investigating how yadargaa may resemble shenjing shuairuo (an idiom of distress resembling neurasthenia), which included some symptoms of depression. Yadargaa is a syndrome that is characterized by disabling fatigue that many recognize through concurrent pain in the heart, chest, back, and joints. Mongolian physicians and shamans believe Yadargaa is the “gateway” disease because when life balance (khii) is lost, then you develop yadargaa. It is closely linked to Tibetan Buddhist medical frameworks that view an increase in humor khii (rlung in Tibetan) that causes the nervous system to deteriorate. In Mongolian medicine, all other forms of illness, such as secondary diagnoses, come from yadargaa. In The Wrestler’s Second, Yadargaa patients described symptoms common among people who experience debilitating fatigue, such as dizziness, trouble sleeping, blind spots, tinnitus, headaches, numbness in the face and extremities and increasing blood pressure.

At the time, there was increasing awareness and discussion in medicine about Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—a complex chronic illness that causes myriad conditions, including disabling fatigue, memory inconsistency, sleep issues, trembling, and myriad other symptoms. Brandon wondered if yadargaa was a Mongolian version of ME/CFS, which was primarily diagnosed in western biomedical and cultural contexts. He was curious whether this construct of ME/CFS (and related symptoms) was a natural category, meaning it was a condition that upheld its character across contexts (even if communicated by different names). Was this caused by a virus? Bacteria? Environment? Political oppression? A combination of these? Brandon traveled with his brother Holbrook Kohrt (a medical student) and his best friend, Bob Koenig (a filmmaker), to make a film about yadargaa and to conduct a combined ethnographic and epidemiological study of the condition.

At sixty-nine years old, Tsoodol resided in Ulaanbaatar with his wife and granddaughter. His eight children and 23 grandchildren lived nearby. Since he’d left his work in wrestling, his family’s income fell and his social status dissolved in the new economy. This economic transition of the state as well as some family problems had an extraordinary impact on Tsoodol. A few years before, his son had passed away, and the family lost his income from steady work. His daughters had looked for work for years but struggled to find it. He said, “In capitalism, if you have money, you can buy a job. We have no money so our children have no jobs.” This economic stress and frustration about the broken economy was fundamental to Tsoodol’s frustration.

Tsoodol’s wife described that he was constantly complaining of yadargaa. That his blood pressure was high and his back and neck were stiff. She remembered, “During communism my husband was healthy. Now he just has complaints.” As the Soviet Union fell, people scrambled to understand how to adjust to capitalism’s grip. At the same time Mongolian doctors and traditional healers discovered that yadargaa was increasing throughout the country. “To be healthy, every aspect of your life must be in balance,” a clinician in Mongolia explained to Brandon. Another explained, “It’s from an imbalance from working and relaxing.” In this way, it is a cultural construct of imbalance—of pushing too hard and recuperating too little—in a way that disrupts the body’s equilibrium and affects one’s vitality (khii).

While Bob was busy filming, the Kohrt brothers spent hours talking with yadargaa patients, health professionals, and community members. Brandon Kohrt was struck by the fact that it was not only patients who reported yadargaa but also healers in traditional Mongolian medicine and Russian trained biomedicine (neurology) regularly diagnosed patients like Tsoodol with yadargaa. Brandon told me, “And when somebody had a stroke and just hadn’t recovered well, they didn’t feel they had the same role in the family” or the same role in society. “We were struck by how the sociocultural context was as important as biology, or the psychobiology, as I call it,” Brandon said. “They were able to hold both the social context of that meaning and the biology together.”

They also collected a survey of nearly two hundred people in rural and urban areas. They combined the stories from people with data from a large range of people that provided an ability to capture how common yadargaa was and among who. One in two people they interviewed reported yadargaa, attributing the condition primarily to the economy and culture change in the wake of communism. This was uncommonly reported by those who didn’t report yadargaa. Like Tsoodol, most people were preoccupied with limited work opportunities. Most of these people lived in urban areas, and were women or older residents.

The survey communicated that the strongest complaints were somatic, including fatigue, pain, and swelling. This made a lot of sense to Shaman healers and physicians trained in both Mongolian and Russian medicine. Numerous hospital wards had wards for medrelliin yadargaa, or “nervous fatigue” and this concept was associated with the Russian construct nevrotz (neurosis). It’s also closely linked to myriad other conditions of the nerves around the world the explain a multi-systems dysregulation of the body. Yet, as opposed to how complex chronic conditions are sometimes perceived in western biomedicine, yadargaa had important clinical salience in Mongolian medicine: neurologists in Ulaanbaatar told Brandon how patients reporting yadargaa were generally more susceptible to heart disease because their stress tolerance is lower, they were more likely to get a stroke and not recover from it, and were more likely to have liver problems. These were systemic issues that centered on their imbalance of the nervous system.

The filmmaker, Bob Koenig, reflected on this experience, saying that it was fascinating to learn about yadargaa in part because the research team was so unfamiliar with it. It’s not something taught in American medical school—as an idiom of distress, or way of thinking about sickness as a lack of vitality, or imbalance. More simply, American medicine focuses so little about the socio-emotional links between mind and body, that it was unfamiliar to assume those with imbalanced mental health would present with more physical problems. However, they found those who did not present with yadargaa were also unlikely to display depression, chronic fatigue, or anxiety, and fewer than half of the people who were diagnosed with yadargaa did so. Kohrt wrote with colleagues later that, “The experience of yadargaa is so variable that it is difficult, even for Mongolians, to define a single yadargaa.”

The diversity of individual experiences is one aspect of Long Covid and other complex chronic conditions that causes clinicians to scratch their heads. When there is no biological test and no uniform presentation, how do you know whether you’re sick with what you think you’re sick with? For these conditions, much like yadargaa, it’s impossible to pinpoint what biological insults are hidden in someone’s brain, guts, nerves, or tissues. Or how many insults (be them virus, bacteria, trauma, etc) may have built up over the life course to cause the body to tip towards dysregulation. However, what’s important to understand is that this weakening of multiple systems at once—particularly the nervous, immune, and digestive systems—is a core characteristic that truly has limited traction in western medicine even though it is an essential human experience. It is truly the glue that holds complex chronic conditions together—despite the diverse collections of symptoms people collect and experience through time and across contexts.

This is so fascinating! Really interesting to see the parallels between yadargaa and conditions like Long Covid and ME/CFS.